Mike Bartick: Blanket Octopus

The blanket octopus is perhaps one of the most mysterious sea creatures of all times. They are a pelagic octopus that lives their entire lifecycle in the open ocean which not only makes them hard to find, but even harder to study in their natural habitat.

Much of what is known is speculation and the information presented here is gleaned from books, the internet, and further formed by personal observations from having multiple personal encounters. What I have learned is that the blanket octopus is a complex animal with interesting behaviors; from the way they mate and reproduce to hunting strategies and defense. One thing is for sure; nothing can truly prepare you for the moment you encounter one.

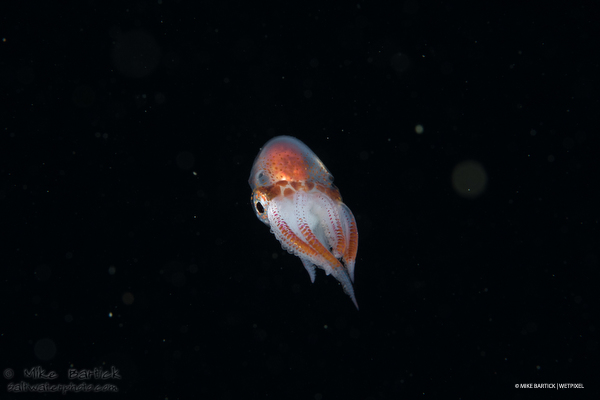

Diving in the open ocean at night allows the interested person to witness and encounter the night sea first hand and in person, there is just no substitute for it. Blackwater diving as we like to call it is conducted over deep water while using a lit downline to attract plankton. I enjoy doing these kinds of dives all over the world but conduct most of them, right here in my backyard; the Balayan Bay, Anilao, Philippines. My first sighting of a blanket octopus (Tremoctopus gracilis) was nearing the end of a dive. I was finning back to the downline when I saw a huge shadow cross our lights. At first, I thought it was a massive jellyfish passing by, and then, as I got a bit closer, I imagined it was a big ray of some kind. Continuing to kick closer I could begin to make out the coloration and body details, and it was at that instant that I knew exactly what I was seeing. It was indeed a 1+ meter blanket octopus, perhaps a bit larger. Its head was as big around as a basketball, and as its arms were pulled in, they made up the rest of the shape that I mistook as a ray. I was at approximately 15 meters (45 feet) of depth and finning hard to keep up and trying to get out in front of it. When I did, its massive purple-green blanket began to unfurl and open.

In this situation shooting with a 60mm lens, you try everything you can to get a shot. I began finning backward to give myself some space, but the octopus kept coming straight towards me. I did everything I could to get a shot, any shot. No one would believe me if I only came back with a story! I shone my powerful hand torch back towards the downline hoping one of my friends would also see me and come down to join. The octopus was casual and orbited our downline effortlessly moving about and seemed as curious about me as I was of it. Looking up, I saw my buddy arriving to join me, and the two of us had our first experience of a lifetime together.

After downloading the images, I realized that our “blanky” was a female as she was also carrying eggs. WOW! I yelled; “Oh my god, this is ## insane!” It was, and I’m sure I woke up my neighbors!

The Blanket Octopus Contains 4 known species:

1. T. gelatus - a gelatinous deep water Tremoctopus, cosmopolitan and found in tropical and temperate waters

2. T. robsoni - Known from the waters off of New Zealand

3. T. gracilis - Palmate octopus-Found in the Indo-Pacific Region

4. T. violaceus - violet colored- Lives in the Atlantic

The four different octopus can are found in almost all of the planet’s oceans, sans the polar regions, but each inhabits a different region. Their lifecycle can last up to 5 years, and they have been observed hunting in the same area for an extended period. Being a pelagic animal means they don’t make a burrow in the sand or create a home as other octopus do. These octopus mates, hunt, feed and thrive in the open water and can roam from the depths of the dark zone to the surface, true masters of their open ocean domain.

Over the last year or so, I’ve been lucky enough to have multiple encounters with males and females and have also been lucky enough to come away with a few decent photos. To have these kinds of encounters requires a willingness to stay out all night on the sea along with a massive scoop of luck.

Unique in appearance and unique in behavior the Tremoctopus are immune to the deadly nematocysts of many cnidarians including the Man o’War jellyfish. It is reported that juvenile Tremoctpus rip the stinging tentacles from the jellyfish then holds them with their lateral arms, whipping them about to sting their prey and perhaps to protect themselves. Many photos show the trailing tentacles and clearly illustrate that this is indeed a typical behavior.

Oddly enough, we don’t have a population of Man o’War jellyfish in our bay which leads me to assume that they aren’t selective and use the tentacles of any venomous jellyfish.

Their reproductive behavior is also quite interesting. The male of the species exhibits the highest degree of dimorphism discovered in any animal. The female can measure up to 2 meters in length while the males only reach a size 2 centimeters, size and weight ratios differ as much as 10,000 times. Like other male octopus, male Tremoctopus use a specialized arm called the hectocotylus which contains its sperm pack. The male only needs to touch the female with this specialized arm as it instantly sticks to her then snaps off, perhaps without her even knowing. The arm then creeps down or somehow finds its way into the ovum of the female where she crushes it, releasing the sperm and fertilizing her eggs when the time is right. Hatching is intermittent.

Like other male octopus having completed his life’s work, the male now dies. However, the female still has a long life ahead, brooding and caring for her eggs until she finally dies from starvation much like other octopus.

Research says their eggs are kept in a “sausage shaped calcareous secretion” but I couldn’t make that out from my photos.

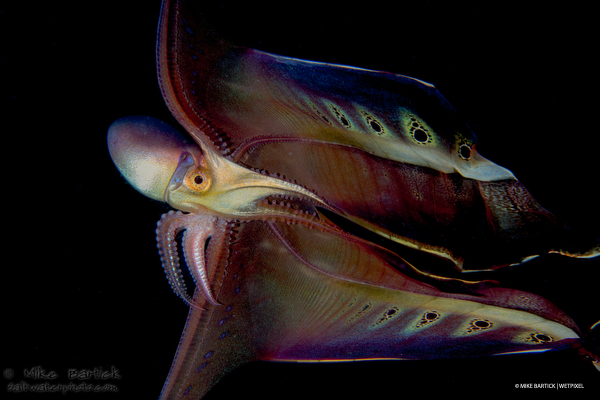

The Tremoctopus gets its common name from the blanket that it can quickly unfurl and retract. When fully extended they resemble “Rocky, the flying squirrel” and fly through the water in much the same manner. The texture of the blanket looks like an exaggerated version of the webbing that a common octopus has and uses to enclose their prey when hunting. However, these guys deploy the blanket to make themselves look bigger and perhaps to hunt and catch crustaceans or other cephalopods like the paper nautilus. The thin membrane is colorful and ocellated much like the feathers of a peacock with a pink, purple-green hue.

They can also detach their webbing to ensnare a would-be predator or to us eat as a decoy while inking. The web is attached to the 3rd and 6th arms of the female, palmated by the 4th and 5th arm. They snap their arms outward repeatedly, tightening the blanket as it moves through the water.

Like a said above, there is nothing quite like encountering one of these majestic animals in the wild. This season has brought us multiple encounters as did the last and I’m looking forward to learning more about these incredible seagoing octopus.

Now get out there and have an adventure!

About the author:

Mike Bartick of Saltwater Photo is a professional underwater photographer who is widely published and also manages the Crystal Blue Dive Resort in Anilao, Philippines.